Ursula K. Le Guin reflects on her Berkeley roots, parenting, and the writing life.

Ursula K. Le Guin has said that her father, Alfred Kroeber, studied real cultures, while she made them up. Indeed, many of the writer’s most celebrated novels are set in intricately imagined realms, from the sci-fi universe of Ekumen to the fantasy archipelago of Earthsea.

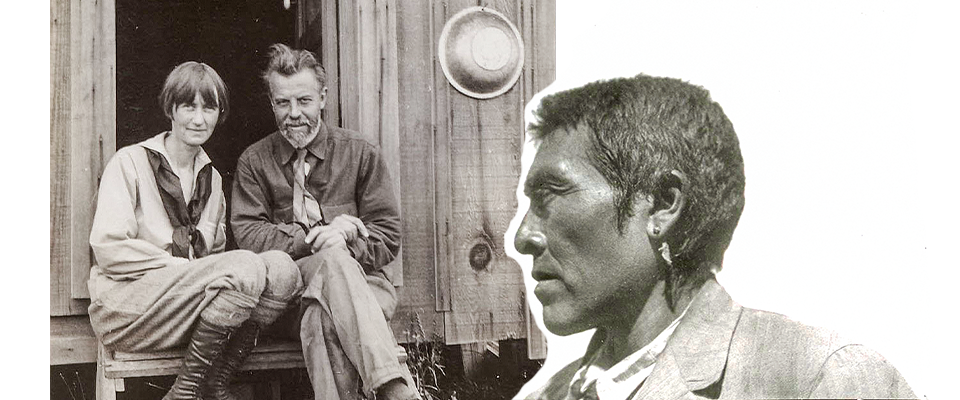

This inventor of worlds grew up in Berkeley. Her father was the University of California’s first professor of anthropology. Kroeber Hall, the campus building that houses the department, is named in his honor. A pioneer of cultural anthropology, today Professor Kroeber is best remembered for his association with and research on Ishi, the man believed at the time to have been the last of the California Yahi tribe. He was even called “the last wild Indian in North America.” That was the subtitle, in fact, of the book Ishi in Two Worlds, written by Le Guin’s mother, Theodora Kroeber, who met Le Guin’s father while she was a graduate student at Berkeley. The book made her famous in her own right. Now in a 50th anniversary edition from UC Press, Ishi in Two Worlds has sold more than 1 million copies.

Le Guin and her three older brothers grew up in a Bernard Maybeck house on Arch Street, not far from campus. She remembers life there as “easygoing and generous” and that the family home was filled with the conversation of “interesting grownups”—including academics, intellectuals, and the members of various California Indian tribes.

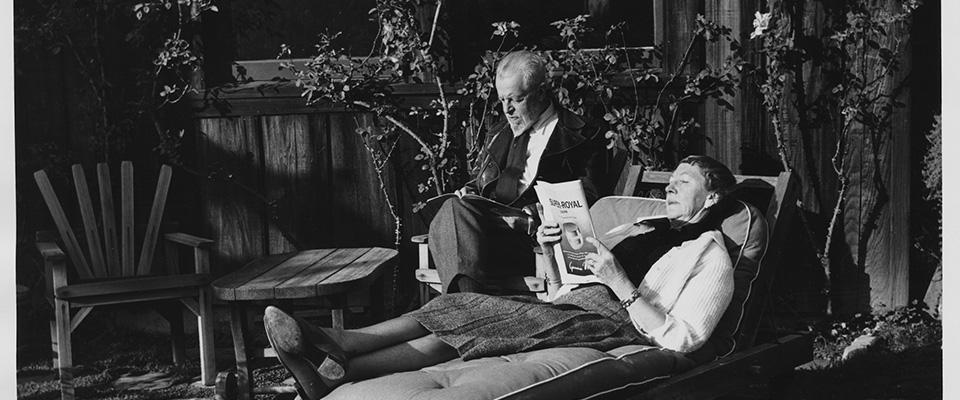

As an adult, Le Guin settled in Portland, Oregon, where she raised three children and wrote prolifically. She and her husband, historian Charles Le Guin, balanced work and parenting by following what she has called Le Guin’s Rule: “One person cannot do two full-time jobs, but two persons can do three full-time jobs—if they honestly share the work.”

Her work has been prodigious. In a career spanning more than five decades, she has published over 100 short stories, 7 volumes of poetry, and 22 novels. Among her dozens of awards are the National Book Award and the Pushcart Prize. She won science fiction’s most prestigious prizes—the Nebula Award and the Hugo Award—five times each.

At 83, Le Guin is still at it; last year she published a book of poems (Finding My Elegy) and a two-volume story anthology (The Real and the Unreal). She also blogs at ursulakleguin.com. Her work, which grapples with questions of power, morality, and gender, continues to inspire dissidents—last year, Occupy Oakland protesters used shields bearing images of her 1974 novel, The Dispossessed—as well as a younger generation of writers. Novelists David Mitchell, Junot Diaz, and Michael Chabon all cite her as an important influence.

California caught up with Le Guin by phone as she was preparing to come to the Berkeley campus to deliver the 2013 Avenali Lecture. The February 26 event, sponsored by the Townsend Center for the Humanities, was entitled “What Can Novels Do? A Conversation with Ursula Le Guin.”

What follows is an edited transcript of our own conversation with the Berkeley native about being a child, a mother, and a grandmother—in short, about growing up and growing old.

Huber: Does a return to Berkeley bring back a flood of memories?

Le Guin: I grew up in the ’30s and ’40s, and Berkeley was a rather small city then. It didn’t have the reputation that it got later of being extremely leftist, liberal, independent. It was just kind of a more conventional university town. It was an extremely nice place to be a kid in. I could go anywhere. My best friend and I, we played all over the campus, and the campus wasn’t all built up yet, you know? There were lots of lawns and forests, and Strawberry Creek was like a little wild creek. It was a wonderful place to play.

Wasn’t Berkeley somewhat bohemian even back then?

There was room for bohemians in it, but it was really pretty middle-class. Not rigidly middle-class like you might get in the Midwest; there was a lot of latitude always in Berkeley, and in the ’30s and ’40s of course it was full of refugees from Europe because the University had a wonderful policy of taking in intellectuals who were running from Hitler or Mussolini. I do believe that influx of brilliant European minds may have stirred the city up a bit.

How would you characterize your parents’ parenting style? How did they raise you?

Well, I think they did a real good job, you know? [laughs] They were very loving and very patient, but they didn’t hover. I wasn’t very rebellious because there wasn’t anything to rebel against, if you know what I mean. It was kind of easy to be a good girl. And I had three big brothers, and that was kind of cool, too.

So, were you children part of the dinner table conversations at home?

As soon as we got old enough. I think ’til we were about 5 we’d eat upstairs with my great-aunt Betsy, who lived with us. I think from about 5 on we were considered civilized. Then Betsy got to come downstairs with us. [laughs] We were all there at dinner, and there was always conversation at dinner. In that sense, it probably seems very old-fashioned to people now.

I was struck by your description of the teenage summers you spent at your family’s ranch, wandering the hills alone. You said about it, “I think I started making my soul then.” Why are experiences like that important for kids to have?

It does seem that, in the last 20 years or so, children get extraordinarily little solitude. Things are provided to do at all times, and the homework is so much heavier than what we had. But the solitude, the big empty day with nothing in it where you have to kind of make your day yourself, I do think that’s very important for kids growing up. I’m not talking about loneliness. I’m talking about having the option of being alone.

If you’re a very extroverted person, you probably don’t want that. But if you’re on the introverted side, you’re not given much room in the world we’ve got now. You’re kind of driven into this whole sociability of the social media. Texting is wonderful for teenagers. I was on the telephone all the time when I was 13, with my best friend. Gabble gabble gabble gabble. I mean, what do teenagers talk about? I don’t know, but they need to do it. Texting looks like a wonderful way to do that, to just be in touch with each other all the time. But I think it’s important that there also be the option not to be in touch for awhile, to just drop out. How do you know who you are if you’re always with other people doing what they do? That’s true all through life; it’s not just kids.

So you would argue that we should try to give kids more space.

Yeah, give them some room. Give them room to be themselves, to flail around and make mistakes. I had lots of room given me, so at least I know enough to value it.

Did your parents encourage you to write?

Not exactly, they just saw I was doing it and they would say, “Hey, that’s fine. Go ahead.” But I was left very, very free. I had encouragement, but no pushing.

Much has been made of the connection between your father’s profession as an anthropologist and the nature of your fiction. How do you think his work influenced yours?

I’m not sure that his work influenced mine, because I didn’t really know his work until I was well into my twenties and thirties and began reading him. But I was formed as a writer earlier than that, to a large extent. My father and I had certain similarities, intellectually and temperamentally. We’re interested in small details, in getting them right. We’re interested in how people do things and what things they do and how they explain doing them. This is all kind of anthropological information. It’s also novel information. It’s what you build novels out of: human relationships, how people arrange their relationships. Anthropology and fiction, they overlap to a surprising extent.

Was Ishi’s story a big part of your consciousness growing up?

No, I honestly knew nothing at all about Ishi until they asked my father to write about him and he sort of gave the job to my mother, and then she began researching him. This was in the very late ’50s. Ishi died in 1916. I wasn’t even born until 1929. My mother never knew Ishi. It was something way back in my father’s life, and it was not a happy memory, I think, because of the way it ended. No. He had to feel very bad about the fact that Ishi died of white man’s TB. My father did not reminisce. He wasn’t one of those people who talked about old times. But I think there was some pain there that he didn’t want to go back to. You know, he was out of the country when Ishi died, and that always—they were friends, after all. That’s always hard, to feel like, “I let him down.” This is just guesswork on my part. He didn’t want to talk about it, and it’s not the kind of thing I would’ve asked him.

What do you think about the way that Ishi was treated, and his relationship with your father?

That’s two different questions. One, the relationship was, as I can understand it, a deep friendship within this curious constraint of their sort of formal relationship. Ishi was an informant and an employee of the museum, and my father was a professor. It was a more formal age, remember. The general question of how it was handled…. You know, I have to say, I think they did about the best they could in the circumstances. They got Ishi a job. He had work to do within this white world that he’d been dumped into. And a place to live, which apparently he liked, and he could meet the public and try to show them what being a Yahi was. I realize it has come in for enormous criticism from generations who have a lot of hindsight and say, “My goodness, they were exploiting him, and they could have done it different,” and so on, but they never convinced me that anybody then knew how to do it any better than they did. But it is a heartbreaking story.

Your mother started writing late in life.

She started writing about the same time I did, professionally speaking. She got published first. And of course she got a best-seller—Ishi was UC Press’s first best-seller. She said, “Oh, I always wanted to write, but I didn’t want it to compete with bringing up the kids, so I had to get you all out from under.” That’s how she felt. And once she started writing, I think she wrote most every day. She loved doing it. Both my parents wrote every day. I don’t; I’m lazier. [laughs]

Your mother sounds like a very feisty and independent, unconventional woman, especially for her era. How did she shape the kind of woman you became?

It’s so complicated. You know, my mother didn’t call herself a feminist, but she gave me Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas to read when I was 14 maybe. Those are very powerful books to give a girl. My mother was a freethinking person. She thought for herself. She read and thought and talked, she was intellectual, so I think what my mother gave me was just the example of a woman with a free mind who chose to be a wife, mother, housewife, a hostess—the conventional life of a middle-class woman. She liked it, very much. If she hadn’t, I don’t think she would have done it. Her mother was a very independent, Wyoming woman. My great-aunt was a strong influence on me, and she was very much an independent Western woman who went her own way. That side of my family, they were strong Western women. There was a lot of independence there.

Where do you think that your feminist consciousness came from, then?

To develop a feminist consciousness, in my generation, it was beginning to grow everywhere, and I was even kind of slow catching up to the early feminist movement. But there came a point in our lives when it was kind of a matter of survival. Again, it’s so complicated, but there has been a very large revolution in thinking during my lifetime. I think we won’t go back to where we were when I was born, which was a man’s world. And, you’re talking to a writer here. Literature was so much a man’s world. And it still is. Look at who the prizes go to. It’s a very slow revolution, and it doesn’t involve blood and killing people and burning bras and all that stuff. It’s just, it’s going to happen. It’s happening.

You have written about the way that you balanced your writing career with raising your three children, and it sounds like…

To call it a balance… It seemed kind of like a madhouse sometimes.

How did you and your husband share this work of childrearing?

That was really the secret, was that I had this guy who could do his job and let me do my job, and then we did our job together, which was bring up the kids. And keeping a house—like my mother, I enjoy it. I don’t think I kept the house very well, but I could keep things going and write.

And so, when your children were small, would you write at night?

Yeah, that’s kind of all you can do. If you’re home with the kids, you’ve got to be on duty. Unless you have servants or something.

I want to ask you about a particular poem in Finding My Elegy, “Song for a Daughter.” Could you just tell me about what inspired that poem?

What’s going on in that poem? Well, when your daughter has a daughter, and her daughter’s giving her trouble, you think, “Oh, boy.” It’s a wheel going around. And the way you feel about an angry 4-year-old: You want to wring their neck, and you love them very much, … and just kind of watching the generations repeat the pain and the love that we give each other, and the fact that the kid never can do anything right, and they also never can do anything wrong. That’s the way it came out in my head. So that is a grandmother poem. It’s got three generations going, and of course it involves my mother, and how I’m sure she felt sometimes, that I never could do anything right. But she never said so. She let me feel that I was doing OK.

Do you feel more or less hopeful about the future now than you were when you began your writing career?

Well, you know, old age does not tend to make you very hopeful. It’s not a hopeful time of life. Youth is. It has to be. And old age—you have seen enough things go to ruin that it gets a little harder to be hopeful. And when you’re watching your species destroy their habitat, as we are doing, it is quite a job to remain hopeful. But then I also have realized, like we were talking about these huge social changes in gender and the relative positions of men and women. The changes are painfully slow, but they have happened, and they are continuing to happen. So there’s hope.

What are you working on now, writing-wise?

I’m not writing much fiction now. I published one story this year, I think. Mostly doing poetry, and I do enjoy writing a blog on my website, which is kind of a new idea for me. There’s a lot to keep up with, and at my age, I haven’t got the energy I had, so I can’t do as much as I used to. I do regret that, but that’s just life.

What do you like about writing a blog?

I got the idea of doing it from the Portuguese Nobel Prize–winner José Saramago. When he was 85 and 86, he was writing blogs. And they’re wonderful. Some of them are political and some of them are just kind of thoughtful. And I thought “Well, wow. It’s a very short form, and it’s very free. Maybe I could do that.” A blog can be anything you want it to be, so it’s good for this condition I’m in of not having the energy to write a novel. You need a lot of strength to write a novel, honestly. It’s a huge job. And even a short story takes a kind of a big surge of energy, and in your eighties, you tend to just kind of run out of that stuff. It just isn’t there anymore. So you parlay what you’ve got. And then there’s poetry, which is always a blessing. And I’ve written poetry all my life, so I’m glad it’s still with me.

Have you ever thought about writing a memoir?

Memoir? No. I’m like my father: I’m not interested in talking about who I was. I’m much more interested in finding out who I am. [laughs] Going ahead.