All you need is a priest, a bandanna, and a strong stomach.

I blame Hemingway. Looking for something to read last year, The Sun Also Rises fell into my unwilling hands. I’d never understood why so many people lived and died by his writing, so I decided to offer him a second chance. There it was: the book that brought Pamplona to the world and then the world to Pamplona. Hemingway be damned; I found myself booking a flight to Spain.

I was going to run with the bulls.

Ever the optimist, I prepaid six nights at Gran Hotel La Perla. What could go wrong? Hemingway himself stayed at La Perla in the 1920s, yes, but it was also in the heart of Pamplona, at the center of the San Fermín Festival, and only two blocks from where my own run would start.

“You need a slipknot in case your bandanna gets caught on a bull’s horn. That happened to a guy yesterday, and he was dragged 60 feet.”

Pamplona is only about twice the size of Berkeley, but a million people flood the place for the San Fermín Festival every July. Every one of them, runner or not, wears the exact same outfit: white pants, white shirt, red bandanna, and a red sash around the waist. I considered skipping the bandanna and sash when I ran. Isn’t it red that notoriously makes bulls mad? Maybe I’d be invisible to them. But dutifully, I put them on. I hadn’t come nearly 6,000 miles to do this halfway.

At 6:45 a.m., I left La Perla, looked out on an empty plaza, a few dozen revelers still sprawled in the grass, sleeping it off. I’d heard there were ambulances every 200 feet along the route, which seemed reassuring at the time. Seeing one waiting silently drove home the real danger of what I was about to do.

By 7:00, I was at the plaza across from City Hall where all the runners gather. The crowd was swelling, 2,000 people were singing and clapping their hands. The excitement and tension were contagious. Maybe too contagious; a few would-be runners changed their minds and slipped out of the plaza.

Someone told me to re-tie my bandanna. “You need a slipknot in case your bandanna gets caught on a bull’s horn. That happened to a guy yesterday, and he was dragged 60 feet.” Gracias, I guess. A Brit asked his buddy, “If you die today, what would you want your obituary to say?” Not a question I wanted to hear moments before running for my life.

Police fanned out through the crowd, removing runners who were too drunk. Fifteen minutes to go; a priest came to a window and blessed us. Ten minutes to go; the crowd got eerily quiet. Runners were absorbed in their own thoughts. People crossed themselves and kissed crucifixes worn around their necks. A few vomited.

I had watched the bulls run the day before from a second-story balcony. The most dangerous place was La Curva de Estafeta, where the street made a sharp right turn.

The bulls were raised on ranches and had never run on cobblestone or made a 90-degree turn at full speed. I’d seen bulls crash the wall at La Curva, runners flying.

I wanted nothing to do with La Curva. I positioned myself half a block away and waited. I heard the rocket go off; the bulls had been released, but everyone around me just stood. We were a few blocks from the corral, so maybe we’d have time to gather momentum before the bulls reached us.

One guy turned his head, saw the bulls coming. He started running. A few hundred people started running. A few thousand. I started running too.

I was running as fast as I could, believe me, but as part of a huge crowd, a single living organism driven by fear and adrenaline and instinct. A huge bull shot past me on my immediate left, snorting. I saw people being knocked to the ground, trampled by their fellow runners. If I was thinking about anything, it was about staying on my feet.

As suddenly as it had begun, it was over. I was in the arena. The whole thing was so quick, and I had survived. As Churchill once said, “Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result.” I wanted to grab someone or shout, “I made it!”—but bulls were loose in the ring, and my gut told me to get out.

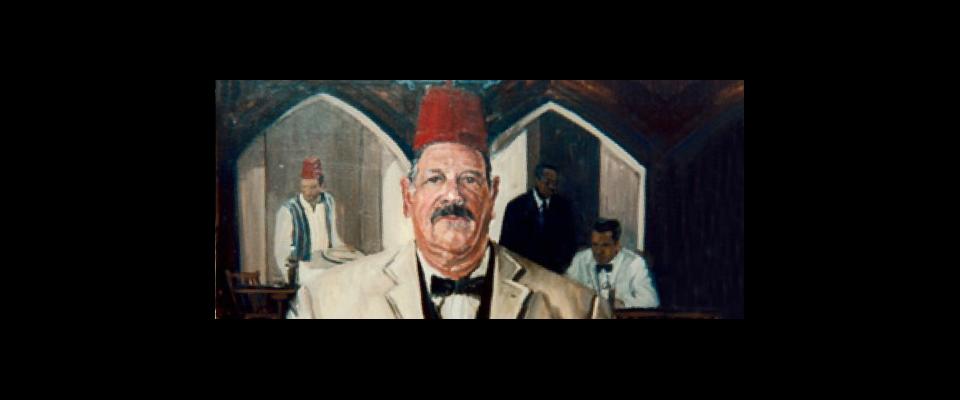

I ended up at the Café Iruña, where my old pal Hemingway used to drink. If you run and don’t get hurt, it’s traditional to drink Kalimotxo, a mix of Coca-Cola and cheap red wine. It sounds disgusting, especially at 9 a.m. It kind of was.

In the end, only five people had been taken to the hospital that morning. As Hemingway would have written it: It had been a good day. No one died.

Former bank CEO Joe Garrett gets and occasionally writes for three different alumni magazines. He saves the best stuff for this one.